I wasn’t running.

If I ran, I would have gotten stabbed by the long red pine needles underfoot. But sometimes I did act like the forest floor was lava when I saw mounds of pine needles 3 feet tall. That meant red ants. And I hated red ants. They bite. Even if I wore my flower-patterned rain boots, the mean, territorial little things could crawl all the way up and over the rim, and take their rage out on my skin. I hated red ants, and sometimes I would kick the mound as I ran by it, watch briefly in fascination as they swarmed, and then scramble away.

Welcome to Sápmi.

So, I walked peacefully through the forest to my stick fort, passing by the castles of red pine needles, hopping on roots, and filling my pockets with the wispy green lichen from any outreaching branches to feed reindeer later; once, I collected so much that my grandma woke me up to see a herd of reindeer just 25 meters from the house. I navigated the paths—left at the split tree, right when the lake became visible, and left again after the big log— until I reached it. A few meters from the trail, my stick fort clumsily came into existence.

I built it on a rock, because the rock was covered in thick soft moss and it was dry, unlike the ground. The moss on the ground in this kind of forest was always wet. Sometimes I could hear, and feel, the squish of water under my tiny rubber boots. Other times the moss would hide a hole or crevice in the rock, and my boot would sink so deep it nearly disappeared completely. I preferred the squish.

One big rock, the size of a dining table, didn’t provide much space, so I put my building materials—big sticks for the main structure, smaller sticks for support, moss to fill the gaps, sheets of bark for the exterior, and flowers I would hang upside down for decoration (just like Ämmi showed me)—on the wet mossy ground or on the surrounding mossy rocks that were deemed unsuitable for the main stick fort.

"Ämmi" is the northern Finnish word for grandma. She makes the best pulla (cardamom coffee bread). She never liked that I wandered so far into the forest, but Äiji, my grandpa, was always on my side. Maybe he knew the forest was home for me just like it is for him; after all, he’s Inari Sámi, indigenous to Sápmi, a region that spans the northern parts of Sweden, Norway, Finland, and a little bit of Russia.

Äiji’s old home is on the peninsula of a lake near Nellim, close to the northern tip of Finland. The little log cabin doesn’t have running water, electricity, or wifi. But the wood stove is perfect for roasting potatoes with dill and simmering rice and milk for creamy porridge; the lamplight bouncing off the walls at night is far more beautiful than LEDs; the tapestries on the walls help keep the place cozy; and the nearby stream keeps the milk and yogurt cold. The home doesn’t have the luxuries we now consider normal, but it does absolutely no harm to its surroundings—which is the very essence of sustainability. The silhouette of the structure has almost become a part of the landscape. It belongs.

From left to right: the cabin, the sauna, and the outhouse.

There was one core moment I will never forget. I had wandered further from the little log cabin than I ever had before, winding through the labyrinth of trees. I remember the way the emerald canopy opened up to reveal a small meadow of glowing long, vibrant green grass. The sun reflected off of every dew drop, allowing everything to emanate its own light. I remember the way the air filled every gap in my lungs, and I knew. I knew this place, dotted with golden cloudberries, was special. Ethereal. I knew I loved this place with my whole being, and I knew I would rip the eyes out of anyone who tried to take it away from me. This was the moment. The moment that my love and connection to nature snapped into place, permanently.

I have no photos of the meadow, but this is "Hilla" a.k.a. a cloudberry.

I went to the forest everyday, perfecting my masterpiece. I suffered through the vicious mosquitos and red ants, coming back to Äiji’s childhood home with twigs in my long bright blond hair and scratches across my tiny arms—just in time to play cards by lamplight. Little me learned quickly that working with nature… it comes naturally. Before concrete. Before steel. There was wood, moss, and tiny hands.

That was ten years ago. This summer, I traced the path ingrained in my memory to find my stick fort still standing (how do you think I got the photos), and serving as a home for woodland creatures.

My return was bittersweet. The red ants still bite—though they seem less painful now—and my meadow still glows…but there are more houses on the lake. Big houses, with fancy docks and bright paint. They don’t belong. We probably shouldn't drink the spring water anymore because oil from their motor boats sits on the surface of the lake; trails and areas normally filled with cloudberries were demolished or fractured by the new roads; and there is more noise interrupting the bird songs. Engines, shouts, chainsaws... I swear, for the love of all good things, if I ever have to see an outrageously lifeless grass lawn in NELLIM… they should be grateful arson is illegal.

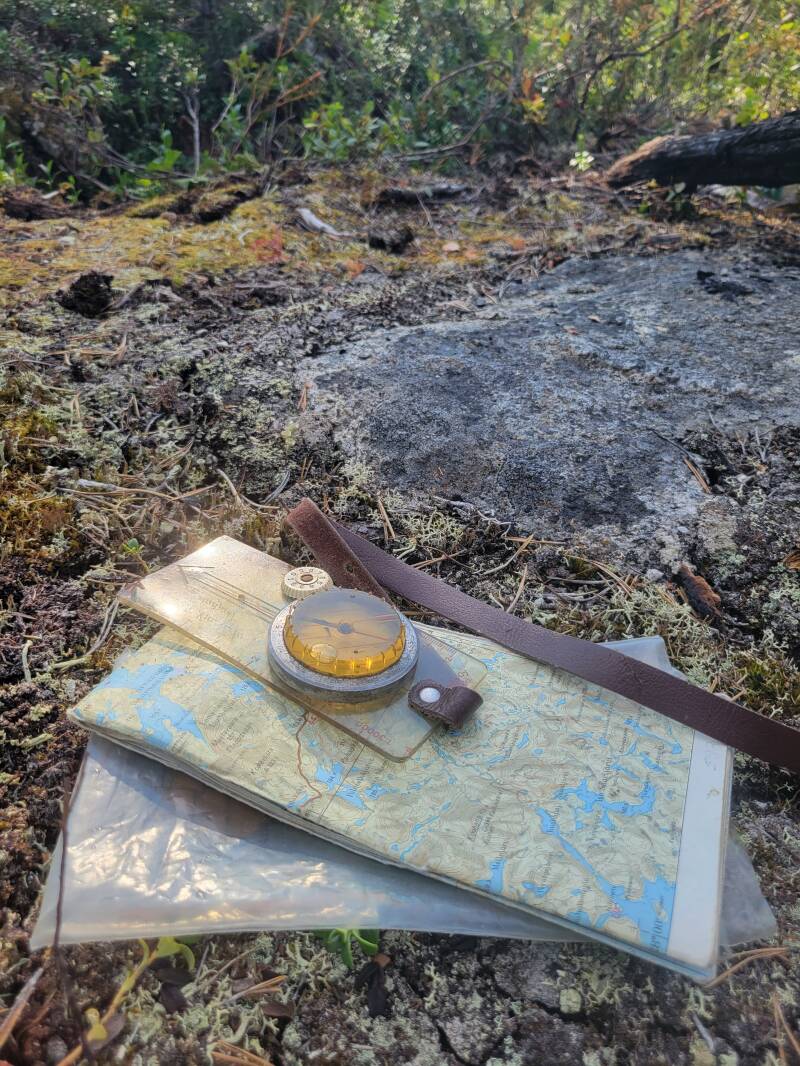

I wish Nellim was as protected as the Boundary Water Canoe Area in north Minnesota. I was there just this weekend, on a 3-day break from civilization… a retreat to my natural habitat of blue lakes and rocky shores. There is an undeniable resemblance between Nellim and the BWCA, and they both feel like home. Many people complain about all the rules that must be followed in the area—no building houses, no motor boats on the lakes, no camping anywhere that’s not already a campsite, no leaving any trace of your presence—but I love and honor those rules because I know that they are what could have protected my special place in Finland.

We will return once more :)

What if…what if instead of expanding into untouched, soul-filling wild places, we can make our cities places that we don’t have to escape from? We can weave wilderness back into our lives and revamp cities with life bursting at the seams. Imagine stepping outside to see the sun glinting through the leaves, patterns of light scattering across the path; imagine biking to work on a trail bordered by wildflowers, and gaping in awe at a night sky full of an overwhelming number of stars. We can grow ethereal meadows on our rooftops.

The University of Minnesota Twin Cities campus isn’t too far from my utopia—you’ll find me laying in the grass in Northrop mall, basking in the sun, and pausing to inhale the sweet smell of goldenrod wildflowers on my walk to the Civil Engineering building—but the same can’t be said for other parts of the city, or most cities in the U.S.

*I do not condone useless biodiversity deserts called lawns... but this one is used for frisbee, photosynthesizing between classes, and pop-up thrift markets.

Plants can do more than make cities more beautiful. They can make cities more functional. Hear me out. City food deserts; the heat island effect; storm water runoff and flooding; air pollution; noise pollution. All of these issues can be mitigated by green things, a.k.a. plants, because they are so much more than decorations or a sustainability prop. They are essential. Humans are not meant to live in concrete jungles—nothing is.

Let’s build cities worth living in; cities where humanity and nature thrive in tandem, at a distance from the soul-filling, wild places in the world. If all goes well, my magical meadow with its golden berries will live for another eternity, untouched by motor oil.

And I will never kick down a three-foot mound of pine needles, the castles of the red ants, ever again. After all, they are only trying to protect their home, same as me.

Add comment

Comments